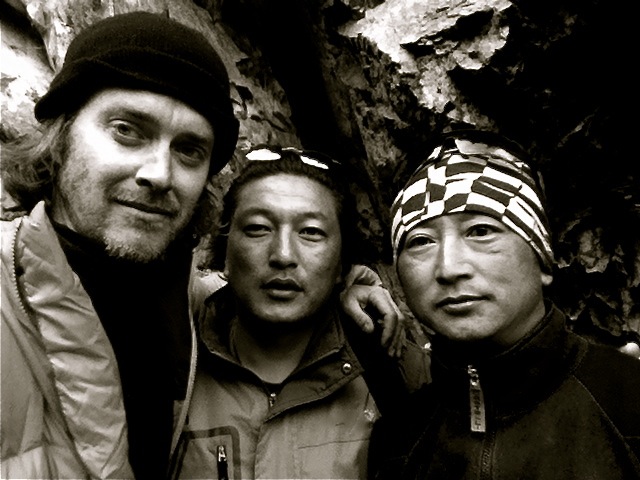

Up until the morning of our departure for the pass, our horseman has been a silent man, enjoying being with our group, and loving Yanpi’s bouts of sharp wit. He has done what any good horseman the world over does: taking care of the horse, our kit and leading us along a route that most have forgotten. Horsemen are part of that old world that is slowly fading along with the trade routes. Their protective guidance, tale telling, and skill sets are no longer really something necessary. Guiding, caring for his mount and feeding Yanpi, Tenzin and I tidbits of the history of the route and of the land we pass through, he is what so many of these local characters are: authentic. This morning, however, he is a man who has taken charge of the morning and is a busy body of motion and news. Silence has given way to authority.

We awake in a morning gloom of dense blue air. No sun penetrates into our dark little valley home. Tenzin was either in full chorus last night with his rampant snoring or entirely unable to sleep. He is a small mess of a man this morning and I worry for his health and his resolve. The coming day will be one of non-stop grinding and these sorts of days require a small reserve of energy…which I’m not certain Tenzin has. He is tough beyond words but still I worry.

All is still and the tree trunks pop in the frozen air, echoing through the valley walls. Our horseman has a fire going long before we emerge from our sleeping bags. In fact he seems to insist on keeping a fire going all night. His head – as it always seems to be – is straining upwards as he looks at the first bits of light of the day. He is, as he often tells, me studying “the sky’s character” (weather) and taking in far more in a glance and a sniff of the air that I can know.

I take my tea into a glade of dry trees a little away from camp and away from the acrid smoke which flavours everything within reach. I like the mornings when I can survey everything from distance and watch the picture unfold. Tenzin is groaning in his morning ritual of rebellion, Yanpi preening himself, and our horseman is issuing us questions, information, and advice. He is a man transformed and I’m happy to see him come into the forefront and assert himself. These are ‘his’ lands that he knows, loves, and fears. We will get back on the main path from our little ‘out of the way’ pad, and head up to the pass. A last little lunch – butter tea, pork fat, and barley bread – will be taken at the base of Sho’La and then we will make the last surge upwards. That is as much of a plan as we need. Our entire team will make for the pass, including our mule who has been sated by a belly of morning bamboo. We pack up all unnecessary gear into our little cave dwelling and cover it up with brush. We will travel light and hope to make the pass by noon and return here to camp.

Yanpi tells me as we begin our ascent that our horseman told him that he was worried about the spirits of the forests and that is why he kept the fire going all night. This wasn’t idle talk to be scoffed at.

When locals were spooked or felt that the natural world’s forces were unhappy, an entire expedition could end. I’d been on the unfortunate end of such occurrences before in the mountains. When locals ‘feel’ something, they do so for a reason, whether it be a divine sensation, a tradition, or simply a colour of the sky. It is not a question of money nor of personalities. And so, one must simply learn to listen and learn and then act. Those who fail to listen to the elements are in for a potentially fatal lesson. Our horseman simply nods us forward. We will be fine…for now. It was to Yanpi’s calm and very local interpretation that I often deferred to such times. He was logical, compassionate, and being from these regions, had an ability to empathize. Crucially too, he knew me and my potential questions without asking.

“We’re fine as long as we don’t have any issues today with the sky. We are off the mountain tomorrow, so we should be fine”. The horseman actually uses the phrase “as long as the sky is happy”.

He doesn’t detail the concerns other than to say, that due to the fact that there were two recent fatalities upon the route we will take, our horseman feels that the spirit world might not yet be finished its ‘sermon’ to us mortal beings.

Tenzin is in rough shape, moaning his displeasures with almost two weeks of slogging taking a toll. He is however tougher than his complaints might suggest and his little body is bent by years of lugging packs. He only differs in that he has learned to voice his complaints eloquently.

The valleys we make our way through are choked tight with rock, dead trees, and frozen foliage. Frozen ‘spills’ where mountain waters once flowed and flooded lie randomly upon the route and we must carefully circumnavigate their gleaming dangers. Light and its effects are strangers here with only minimal rays of sunlight being allowed to visit and the valleys smell of damp cold.

We come to a wide swath of ice that lies in front of us coating the very ground we must cover, and our horseman carefully comes around one edge hoping to lead the mule over a section with more traction. In an instant our mule has started a frenetic dance as its hooves splay and search for a hold on the ice. The hold doesn’t come as the animal slides off to a side ‘gulley’ off to the side tearing a gash in its side and one on its head as it does so. We race to it. It has stood up and is clearly spooked. It will not move and shows us some of its unhappiness by launching a rear kick at Tenzin. The kick whistles wide and luckily so, as that hoof with power would have broken bones at the very least and our Tenzin would have even more reason to be downcast.

Those who have ever said that animals only communicate instinct as opposed to emotion could not have seen that mule’s fury and sense of betrayal, without being moved. Its big eyes speak to its master, pleading, while glaring at Tenzin, Yanpi, and I a moment later. None of us moves for twenty minutes. Nothing will budge the animal and Yanpi and I decide that in ten minutes if nothing improves we will simply push on alone and let the horseman return to camp to rest and deal with the mule’s moods. Whatever our horseman does – or doesn’t do – our mule decides that it will stay faithful to us and without warning simply continues on its way.

Sho’La’s vaunted designation as both sacred pass and deadly place comes from centuries of travel and struggle over its gorgeous lines. In Tibetan the word “Sho” often refers to the sour yak yoghurt that nomads still eat. It is an off-white colour and many point to this reference and its resemblance to the tones of snow as being significant. “La” simply designates a pass.

Those who succeed in crossing the pass are said to have eliminated their past ill’s and sins. For traders and travelers heading to Lhasa it also marked the first of the great snow passes on the way to Lhasa. It is said that many first-time muleteers, having gone through Sho’La’s tempests and eccentric moods, quit (or worse, died) in fear of having to cross more of these deadly passes.

My first journey years ago across its spine took place in the month of May and a team of 6 of us came close to losing two members in a blizzard that lives on in white potency in my mind. The pass is an elegant-faced beast that doesn’t need an alter ego. I’ve been atop its stunning cusp with winds blazing at close to 80 kph hugging the ground in desperation and love of its force while simultaneously marveling at its absolute beauty. It is a place that impacts.

Around us the only sound that raises itself to the ear is the precise sounding ice stream that rushes downwards off to our left. Landscapes like this leave little headspace for other places, people, or even thoughts. Mountains and passes demand everything to be in the very vital ‘now’.

We must pass through this clean silence to access a place that is never without shuddering winds and a shrieking backdrop.

When we exit into the larger ‘welcoming’ valley that marks the entrance to the Sho’La ascent the sun is finally unimpeded to blast us. We take our last tea and snack break before our final push. Tenzin sprawls out on the ground and is asleep in a minute, while the wind scurries about us in an ever-strengthening force. Our horseman squats with butter tea in hand and looks to the pass and tells Yanpi that he and the mule – who I’ve named ‘Amalia’ (a Hungarian name meaning ‘work’) – will not make the final stretch of journey. Tenzin, who we wake, also lets us know that he won’t make the final. Tenzin’s eyes are sheepish when he tells us the news but I know that it is a decision that, however difficult, is a smart one. His body, and more crucially his will, are not in it.

The three of them will remain at our tea site and head back to camp after resting. Yanpi then looks at me with those ever-calm eyes and simply says,“We go”? Yes, we go. Our horseman gently touches both of our arms as we leave with a nod of the head. Go safely. Tenzin tells us meekly that he’ll have coffee ready at camp which only brings a grunt from Yanpi.

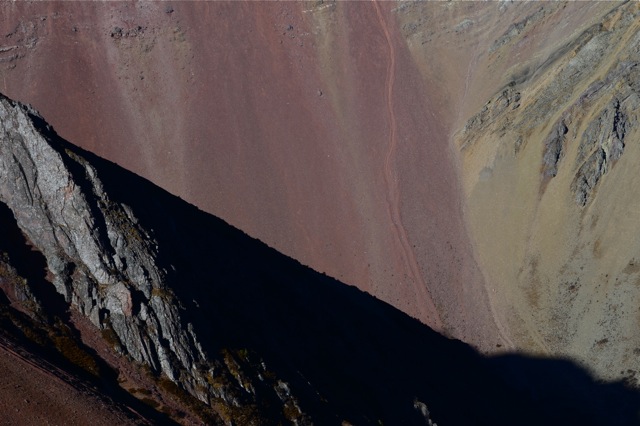

Sho’La, as always, seems “just over there” but that “over there” in mountain terms often takes hours. Yanpi leads us into the ‘red valley’, which sits below the pass and encapsulates a basin. On our western flank a slanting wall of red arches up spectacularly. It dares you not to gaze at it and even Yanpi’s head is turned for long spells as he leads. We have almost four hundred metres of altitude to ascend.

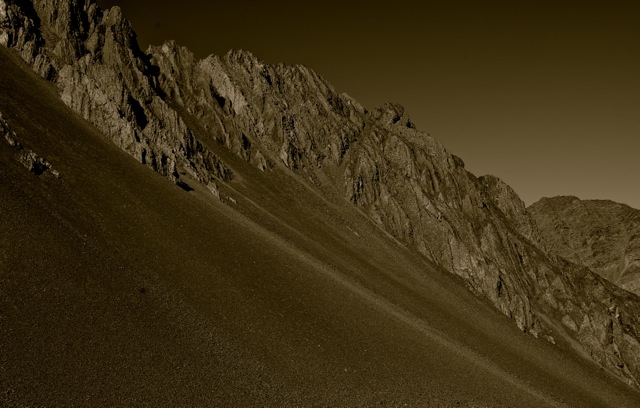

Yanpi on this day opens up about his life, his dreams and worries. They are the worries of a father, a husband, and a man with a good mind. It is as though the mountains have suddenly provided a forum for any and all thoughts to be voiced and it is this sort of opening up that is a welcome thing on an ascent. Heading southwest to the pass we move through the shadows of the northern edge of Sho’La which is barren of ice and snow.

It is the first time I’ve not seen any residue of sleek white. Only the dust puffs of our treading feet. I recall wading through hip deep snow just months ago. The winds are thankfully present and it romps and pummels us. Our last 30 minutes are spent in silence. Limbs and lungs take priority over conversations.

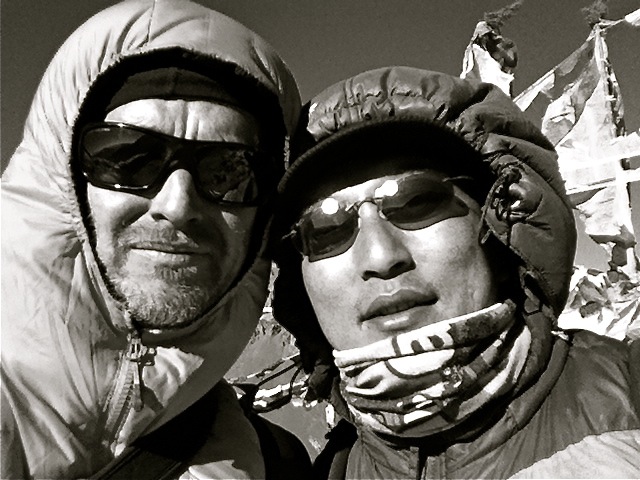

Arrivals seem something almost anti-climactic at times. We are suddenly there on the great pass with its wondrous history of hosting, blowing, and killing. Without snow it is shorn down to its bones looking leaner and edgier. The lack of snow is disturbing. An aspect of the heights in the Himalayan world is that they are inevitably layered in the spiritual world’s colours and ornaments. Prayer flags, mani stones, juniper and even shrines, mark places that in the west one would need climbing gear to access.

We pay homage to the pass and give salutations for our Tenzin, our horseman and even our mule Amalia. We also pay regards to Ngawa and Songjè, two forces who helped get us here but couldn’t be with us now. Yanpi sits facing south cross-legged hunched in the cold winds and snapping prayer flags just staring, while I pace and take in as much of the detail as I can. We spend twenty minutes on the pass before we simply look at one another and move off having been re-infused with energy.

On the way down Yanpi tells me that he was thinking of his daughter when he was at the pass and he felt that he wished she was there with us.

It will take us just over two hours to get to camp. We are racing against the winter sun’s disappearence. We move fast, skipping over logs, along rocks and through branches. Descents on slick freezing stones, in shadowed light don’t make for a relaxed journey.

We pick up the scent of familiar smoke at one point and though the light is dying we recognize our little turnoff to the camp. Tenzin is tending fire and smiles at us. Our horseman looks us over top to bottom, welcoming us, and Tenzin shoves a coffee at us in our tin mugs.

We pick up the scent of familiar smoke at one point and though the light is dying we recognize our little turnoff to the camp. Tenzin is tending fire and smiles at us. Our horseman looks us over top to bottom, welcoming us, and Tenzin shoves a coffee at us in our tin mugs.

Tenzin’s snoring is in full and muscular chorus that evening and I wander along the glacial stream which is lit by our fire’s glow. Somewhere in the woods an animal crashes through the underbrush and then all is still.

A photo shot by Tenzin of my face as we negotiated icy roads on our way back to ‘Shangri-La’. More stress in that look that in nearly two weeks of trekking

Thank you for sharing your amazing journey. That you reached your destination and stayed for 20 minutes says so much. Maybe that it’s so much more about the journey than the destination. I could almost ‘feel’ the aches, stress and cold that you write about as well as the beauty, peace, humour and friendship. And afterward, you survived the icy roads!

Kim