Another of the faces that stay with me. A nomadic pilgrim, having just dunked her head in a stream wipes the remnants off. Toughness in the mountains is a minimum requirement and it is never something flaunted...it simply is

The kora, for Buddhists and Hindus, circumambulating in a clockwise direction follows the apparent movement of the sun. The sun in question is now hidden as we wake in the camp of Chube’ka. Tucked into the valley there is only cold air seeping out of the earth and into us. Sleep was touch and go, though there are no immediate reasons as to why – sleep isn’t always a comforting time in the mountains.

Reke has slept badly and his normally patient face is tight and explosive looking. Michael wants a tough day and he is impatient to push the bodies into the redlines. Kandro looks at me over tea telling me that today will be “up, up, up”. Drolma is ever-smiling steering our morning with liquid, food and the kind of quiet care that women the world over can provide. Our big man Tseba sits quietly away from the fire with a bowl of tea with those big chocolate eyes straying into the skies. I find his moods a good gauge of the days to come for us.

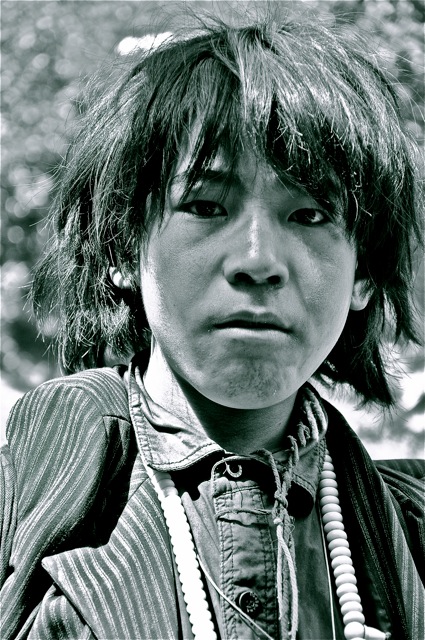

Pushing the pace we make good time catching and then falling into pace with a large group of nomadic pilgrims, led by a slightly deformed young man whose strengths seem realized in the ascents. He is a mess of dust, disheveled hair and of magnificently wild eyes that flick everywhere in a moment. He wears a suit coat slung as only a Tibetan can sling a piece of clothing: loose, one arm out and tied in a casual knot at the waist. The young boy’s back is hunched and one arm appears longer than the other. His being looks like he has been hunted for his entire life. He moves with the uncanny smoothness of a cat. It is as though his distorted body has become his supreme vessel. I suspect he pushes himself to punish and purify his past and future lives respectively…karma, in his mind at least, may be to blame for his malformed back. I cannot stop looking at him.

The young man that made such an impression on me. Bent by disfigurement, his simian strength and agility ate up the kora in gulps

His chin seems perpetually puckered as though he has been engaged in the effort of simply living. And of course I am aware that I, in my way, I maybe creating an entirely different picture in my head than he really is. I cannot help but feel though, that every pilgrim group we encounter has a titan or self appointed guardian leading it. This face is one that stays in the mind long after the features have disappeared.

We make it up 1000 metres before lunch to Nang Tong La, lunching at the auspicious ‘Karmapa Spring’. Around us are entire clans feasting away in a yellow plastic enclosure…and there he is, the misshapen boy running every which way preparing, arranging and creating for his band of travelers. Our eyes meet and I smile and he doesn’t, but there is a millisecond of something from those haunted eyes before moving on.

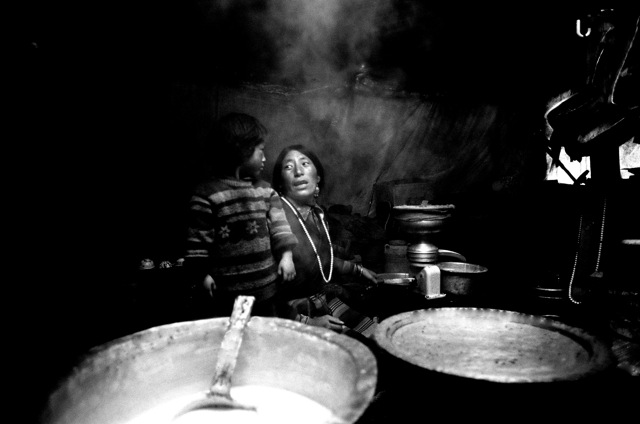

Lunch tents became populated during mid-day and would empty out in minutes only to wait for the next day's hungry

Moving on we make it to the town of A’bin, coming down those 1000 metres and more to arrive in a tiny town whose main street seems to be laden with pilgrims cooking and stretching out. Now we are beginning to see the strain of the kora. Eyes are cracked, hair is filled with night’s little things and there is more of a silence to the groups. The odd figure walks with the ‘blister limp’ and the smiles are now more smiles of resignation than fresh joy.

A’bin is a town that has opened itself up to (or been opened up by) the moving bodies. Beds, cooking facilities and supplies are all available for the ‘walkers’. Pilgrims line the streets relaxing, while locals line the streets greeting the surge of pilgrims.

Along the trail, simple things become special things. Here I chomp down an apple which turned into three apples and gave the day a nice sheen

We ‘camp’ in a huge home, laying sleeping bags in a corner after an epic meal and some epic sips of arra (whiskey). Drolma lays down a few choice words for Kandro about the amounts he will not get to consume. He disappears for a ‘walk’.

Barely a metre wide, an ancient trail still sees the hooves and feet of travelers. In many mountain corridors these trails are still the only way from one isolated place to another

Nice as it is to sleep within walls, I feel slightly claustrophobic and long to get out to the fresh air and unencumbered sight-lines again. We wake to take a pathway, less than a metre wide, that lies in wait. We traipse along its length descending, and with the descent comes my old nemesis, heat. Once down in the valley we are literally encased in walls of tawny coloured stone.

We have a forty-kilometre day ahead of us through hot valleys along a river that has long held a warm place in my heart, the snaking and devilish Tsa Yu River (Tibetan: Tsa Yu Chu). Known for its bends, there are tales and songs about its length and about the spirits that populate its watershed.

The moment the horizon opens up beyond the river valley a hint of what lies beyond breaks into the sky

Kandro is in bullish form today loping forward with his primal frame letting his body do what it is good at. Like many truly ‘tough’ men, Kandro has no need of exerting any kind of vain proclamations of man-hood. He is a smiling, mountain machine…with a soft spot for dogs. A lithe and quick footed dog has been following us for over an hour, keeping a safe distance. Kandro clucks his tongue and encourages the canine to stay with us. At one point Kandro stops me in mid-stride, opening my pack (which contains our food for the day) and gets out some sweet bread sticks and throws them to our silent friend.

We are walking through a sweltering day of dust along a road. The only traffic is a series of dump trucks which courier pilgrims along to the town of Jana further up. They beckon us onto the vehicles but we are set on walking the route. No pilgrims walk the route we are now on, opting instead to take a 2 hour truck ride northeast, offload and simply continue on foot.

A young mother, whose knees were bent with fatigue carries her baby along the kora. Entire clans locked up homes to come from afar to pay homage to mountain

Kandro leads us down a path towards the Tsa Yu River, points to a series of natural springs which gush out their streams into the river below…and promptly begins undressing. Bath time!!