Guest blog post for David Lau’s Asha Tea House in California on tea’s very simple and understated origins in southwestern Yunnan – Pulang Mountain – here

A bus, A Cherub and More Hills

Gansa is no more – back to Xining and onto one of those bizarre 15 hour bus rides that become like their own little worlds. Bunk beds and cell phones everywhere and a populace of forty-five or so that either gets to know one another or tries very hard not getting to know one another.

Michael ponders his new living quarters for the next 15 hours – a bunk that is 30 centimetres too short for a full stretch and a mere sliver wide with only a small bar preventing a two metre plunge onto the floor

Our destination is Zado (not Dzado nor Zadoi but rather a smaller town off of the main route) – continuing our great southern plunge – but our bus direction is towards the Khampa stronghold (within Qinghai) and ancient market town of Yushu. Also known as Jyekundo it remains true to its Khampa (eastern Kham region) routes in populace, appearance and passion.

We ease stiff bones off the bus just as cold light attempts to stir the day. We exit at Qingshuihe (Danda to locals). Wrapped bodies stir, crooked dogs stretch out their thin frames (as we are doing) and the cold seems to be in everything.

Two hours later we step out of a small van and into the cold downtown of Zado. Rain, which would become snow in only a couple of degrees less, falls in uneven sprays of mist.

Wet and muddy Zado welcomes us to a barren bit of civilization set amidst highlands and nomadic valleys

It is amazing what the sky’s moods can do to a landscape. The rolling hills are green, but an overcast sky gives the entire area a grey filtered coat. Though technically still in Qinghai, the bodies here are bigger boned, wider and there is that little bit of recklessness in the eyes that remind me of Kham which rests below and to the southeast. It is comforting in the way that the more tangible elements in life are – I’ve always found it easier to trust that which is seen, which is felt regardless of intensions.

Nomads are never far and their duties never finished. Here a nomadic woman collects yak dung for fuel as trees are absent above four kilometres in the sky in these parts

Our host family lives in a muddy field in a walled-in compound tucked away behind mortar. The requisite Tibetan mastiff is tethered by a chain that could haul an automobile and the ‘main man’ himself is built in similar proportions to the mastiff. He wears the ‘alun’ – a long silk length of immaculate black tied into his long hair, wrapping his locks into a weave on his head – that is often favoured by the Khampas of eastern Tibet. It is worth describing him because of his absolute audacious charisma in this little idle town. Fastidious, wide, with a head and neck that threatened the seams of his shirt, he is a series of parts that didn’t seem to belong together – such is charisma. Immaculate, brutish, eloquent, direct, powerful and self deprecating – all of this was visible to Michael and I within minutes. On his meaty face there is a delicate moustache breaking up his block like head and civilizing him (or ‘villainizing’), but it is obviously a thing of pride as he often lifts his huge paw and pats the few whiskers down softly. With all that he displays, there is still the sense that he is holding back so much more – he is magnificent. It is such characters that gave a day a little lift and a bit of colour.

Two new friends – of the three of us, Tupten ‘the bull’ (right) is most crucial to the tale. He was never without a little munchie tucked away somewhere and his flare for life will remain with me for sometime

The town of Zado itself seems at first glance miserable but all around us there are pockets of noise and life and of course the nomads which can legitimate a place for me instantly. Their splashes of colour, the fierce but warm faces and their guttural clicks and clucks as they communicate…and their signature motorbikes which seem capable of carrying the weight of the world.

Michael and I track down a dumpling shop, which always seem to fill our ever present voids of hunger. It is here, that we often communicate and strategize our next steps. It is where our observations, our highs…our questions are randomly released. All comes out over dumplings.

I am always curious in these towns with so many huddles of men sitting around, at what all of these people do. For the Tibetans much of their life is seasonal, making their fungus profits in the spring and moving their herds of muscular yak in accordance with the sky. Making the rounds with our massive host of the moustache we are treated to curiosity, reckless and completely free smiles and the odd little body peering around from their mother’s woolen layers.

One of the figures which marks my travels. I swung between calling her ‘the cherub’ and ‘the little goddess’…regardless of ether title she swilled butter tea down in amounts that stunned

One of the extended family that we are staying with (though not sure who) has a little girl who has one of the most beautiful faces I’ve ever seen. Plump, broad and already showing signs of being indestructible, she has both innocence and cleverness in her eyes. Watching her down bowl after bowl of butter tea I marvel at her…she is utterly fearless. Her face is dark and Asian but there is something universally familiar about her, almost divine – a rolly-polly little goddess.

We come to a nomadic series of valleys outside of town, passing rusted out abominations of gold mining equipment – left to rot in the middle of a river. The valleys are pathways leading to other pathways bending, reaching ever higher -everywhere are yak.

Our host, Tupten, strokes his moustache a few times before introducing us to a household. The woman of the house – and there are always women of the house – is thickset with shoulders like a bull, and opens her home and life up to us without second of hesitation.

One of our many hostesses – here she assists in ‘spinning’ yak wool making it pliant enough to use for ropes, tethers or any number of needs around the homestead

Kids gather with unkempt hair, dirty fingernails and gorgeous smiles. Carefree with scars already adorning their faces, this is the next generation of nomads. They do effortless handstands and have the kind of innate athleticism that comes with fearlessness and understanding.

Tupten proves as adept with the nomads as he is with us. There is no pompousness and no treating anyone as beneath him. He effortlessly imparts joy.

A gang of nomadic boys shows up for some fun – for a life of toil on the land there are many moments of pure collective joy to be had

As always the combination of elements rubbing against us, and real time life being lived brings a sense of comfort. We ease further into the deep valley’s belly as cold clouds form and rumble.

Rain comes as we sit within a nomadic tent with a family, taking back bowls of tea. Tupten laughs at something our host has said and the feeling that all is well, with a fire, friends and some tea is strong.

One of the brilliant ‘musts’ within nomadic tents – a clay hand-fashioned stoves – with multiple openings for cooking multiple items at once, though here the emphasis is on kettles for tea

There is a discussion being had about school – our host adamant that going away to school to get an education is vital, while the son has the expression of someone who is quite content to remain at home. The lives of nomads, while humbling in the physicality of their environment seem in many ways wise. Once the elements are dealt with (and one learns to survive them), the days pass by for many with good unprocessed food – yak milk and yoghurt are laden with amino acids, minerals and vitamin A – and people who you know absolutely and who are close. I remember a nomad from the Niarong (Hsinlong) portion of western Sichuan once telling me, “if one survives past 12 years old, one will live a life of sun and movement”.

Poverty here takes on different proportions and appearances. Nomads often pity the city dwellers who live in shacks, eat nothing and cannot breath air…

Outside of our warm tent, the rain changes tune and direction…but doesn’t cease.

Mr. Lu’s Dong Ding – A Flight of Taiwanese Fancy in Qinghai

Days of wandering the mountains and the sturdy nomadic corridors of Qinghai and Gansu have brought Taiwan’s world of lush Oolongs to my mind, though there are little external or obvious links…perhaps it is simply a ‘thirst’. Years have passed since my taste buds were last on the little island of volcanic greens and some of its famed tea offerings.

But, this is what makes a bit of unpredictable nostalgia and fantasy so enchanting: that it can strike at any time brought on by who knows what. To deny these mental wanderings is to deny what the brain and blood has lived, and this is especially the case with that permanent in my life, tea. Taiwan was after all where my tongue and brain were laid bare and demolished and ultimately guided and hooked by tea.

In this case, all that can be said is that sitting watching a storm roll in, with yak peppering the green expanse in northern Qinghai Province the smell of ‘wet air’ and a storm brings to mind rain…and in no part of the world that I’ve been, has rain – and its almost septic smell – made such a powerful impression as it has in Taiwan.

So, I sit on a grassland smelling and feeling this impending tide of water come and in slips a memory of a tea session of magnificent amounts of Dong Ding (aka Tung Ting). Dong Ding a small village and mountain sits at the western edge of the central mountain range running vertically through Taiwan, in Nantou County – a county that is literally imbued with tea – nothing moves, boils or breaths that isn’t somehow linked to the green leaf. It was also close to the epicenter of the ravaging 1999 earthquake, which ripped apart Taiwan. Within the Dong Ding region, almost sixty percent of the residents are tea farmers and the other forty are no doubt selling, supplying, transporting or simply knocking the stuff back by the litre. Even after the earthquake, devastating as it was, people got on with the business of tea.

As always my ‘delivery’ and arrival to a tea sanctuary is in part due to a good friend. In this case Lynn Wang, of Wang de Chuan Teas – an old and respected tea clan of Taiwan – has set me up with a demi-god of Taiwan’s tea world, Mr. Lu. Quiet and understated (at first) my host welcomes me with hospitality and meals that both humble and set the organs into a kind of insulin shock.

It doesn’t take long until we get into what its all about in this region – tea – specifically Dong Ding.

Near the town of Luku, lying around the base of Dong Ding Mountain itself. Though aesthetically pleasing these comfortable rows lack much of the shade needed for tea bushes to grow 'best'

Mr. Lu actually owns tea gardens, an entire ‘mountain’ in fact, and has the kind of neurotic knowledge of tea that puts him comfortably in a bracket that makes up for any idiosyncrasies. Like many true tea people, there is an initial hesitation and assessment period with Mr. Lu while he sorts out whether I’m an imbecile with good intentions, someone genuinely interested in tea or an accidental traveler.

With intentions and credentials (mine at this point is simply of a devout drinker) out of the way we travel to his ‘tea gardens’ – young tea bushes being carefully tended to so that after three years – which is a sort of minimum in this part of the world for a tea bush to start producing decent teas – he will be able to harvest and sell his teas. Patience and care are crucials.

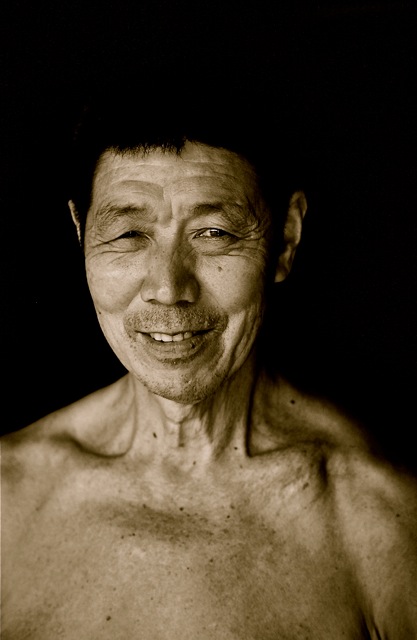

Crucial and under appreciated are the tea producers – men and women who actually take the harvested tea and get the green leaves to their eventual desiccated form. This tea maker at 70 looked years younger…attributed to his tea consumption

We walk through a tight series of hills that have nubile tea bushes planted in a casual sort of organization. Mr. Lu’s lean body and fine features betray only an intense concern for his children as he stoops, turns and once in a while utters something unintelligible. He makes a point that is made often within the sanctums of tea drinkers, that it is vital to know who is growing and producing a tea. This is, in his words, as important as knowing the geographic location. Attention to detail and an ability to create consistent teas are of prime importance. Teas grow but in this part of the world, they do not create themselves.

“Dong Ding is one of Taiwan’s classic Oolongs, and you don’t try to enhance classics…”, he tells me, though later on in our relationship I am to find out that he can and does ‘tinker’ a bit with this truth. He slips in another tidbit about the ‘wheres’ of a tea’s origins. South facing tea hills, for him, are always superior, providing they have ample shade, while North facing tea hills often create teas that are ‘too cold’ (making reference to tea’s ‘ying/yang’ aspect). Already considered within China’s great and ancient medicinal encyclopedias, as a ‘cool’ or anti-inflammatory element, tea can actually become too ‘cold’ when grown in ‘un-thoughtful locations’.

Where we march through is a little over eight hundred metres altitude, which allows for Taiwan’s famous humid mists and fogs to cascade over the leaves in cool unending waves.

Dong Ding or Tung-Ting, known to the occidental world as ‘Cold Summit’ is a tea that has, like many, has been the unfortunate victim of western attempts to ‘re-jig’ and orchestrate a more marketable ‘sounding’ product. Dong Ding has often been titled as ‘Jade Oolong’, no doubt because the aesthetic ring is thought to enhance the ‘Cold Summit’ moniker.

Whatever else it is, Dong Ding tea is not a Jade Oolong. Dong Ding’s grow (or should) grow higher and in cooler climes, which slightly slows the maturation but ensures a deeper and more genuine taste. Dong Ding’s are also harvested only twice a year – as opposed to many other more heavily marketed teas, which are over-harvested, some as many as a half-dozen destructive plucks a year.

Mr. Lu’s features become disdainful when the subject of fiddling with the nomenclature of tea comes up. Like any true impassioned student, his ire is combined with a kind of seething hate regarding ‘trends’ and obfuscating something that is inherently simple.

Much of his sage and impassioned monologue has been forgotten over time, but I do recall with a pleasant shiver a particularly sharp comment (with an accompanying grimace) when he attacked the forces that seek to turn tea into a ‘product’ with no basic knowledge imparted. The words “fraud in the world of tea is to be expected, but there should be heavy punishments dealt out to those that attempt to deceive this ancient right to consume tea in good faith”, or something very similar made a huge impression upon me – enough that I was madly scribbling away while he raged. Words were meaningless out of some mouths, but mouths that sipped (and knew) tea, like his, provide snippets of brilliance – not only about sales, but also about tea’s philosophy.

Though altitudes are given much importance – higher altitude “high mountain Oolongs” command increasingly restrictive prices – Mr. Lu scowls a bit at this as well when finally we sit for a ‘series’ of teas. Though Dong Ding likes the high ground – up to a thousand metres, Mr. Lu says a real Dong Ding can grow as low as six hundred metres, though as he talks it seems to distress him to try and qualify exact details and numbers. “Altitude is important, but if the production process isn’t exact, what use is altitude”? Dong Ding does have a reputation though along with other high altitude teas – in Japan they are known as the famed ‘takayama’ – ‘high mountain’, and revered for consistent quality, though Japanese still much prefer their own stunning greens and Pu’erhs.

We sit in a chaos of plants, tea, papers and calligraphy. Mr. Lu’s office is comfortable in the way that a place is at peace because of a complete lack of pretention. Tea pots sit in an apparent contradiction to the rest of the room. They are lined carefully upon a medicine chest that has been kept immaculate.

Mr. Lu has rolled up his sleeves and there are two other guests. We will, we are told, on this sweltering afternoon try three Dong Ding’s – all made by the same tea master (his name isn’t even mentioned). One is a new spring (April) harvest, one a lightly roasted Dong Ding (last year’s November), and the last whose contents are in a handwritten labeled silver bag.

What many tea growers say is a must for a true tea garden – bamboo forests which supplement minerals, provide shade and add a dimension of green

Mr. Lu’s hand hovers above it and there is a slight softening of his sharp features – clearly a favourite child.

Our first round of the newly harvested spring tea is a green, fresh palate cleanser that, though good, for me lacks any kind of biting power that inevitably sets my tongue alight. We cruise through this with Mr. Lu watching us carefully but making little in the way of comments. Yes, it is light and unobtrusive but my own buds are waiting for something that drills through the skin of the cheeks.

Mr. Lu prepares the first roasted Dong Ding which ups the tempo a little – the longer baking time giving a little more that the tongue can grab onto, though the finish is still classic – sweet and mild. One of the tea drinkers beside me makes a comment that this tea is more “interesting”. Mr. Lu still says little other than baking or roasting can hide inferior teas that are picked too early or poorly produced…still, the tang with this one is almost narcotic.

Of course the third tea has us all in slightly idiotic states of expectation – the saviour has come! I notice that Mr. Lu seems to be measuring the tightly rolled balls with a tad more attention and conviction. The coiled balls are darker than either of the two previous sippers. After rinsing the first pot, we are gifted an inhalation or two. There is no light essences or perfume to this smoky almost acrid vapour waft. Whatever else the tea is or isn’t, it pounds its attributes out up into my sinuses. Mr. Lu is smiling as we have all evidently detected something sublime inside the tiny-lidded Yixing pot.

One of the unsung heroes of the entire tea process – and a profession that is seeing less and less aspirants – the tea picker

We reach the third infusion silent. Smokey, light and a taste that doesn’t stop sifting through the mouth, it is a tea that hits parts of the palate that are rarely enthused. Mr. Lu is no longer at all concerned with us…he is fixed on the cup and a point somewhere in mid-space. He knows what we are consuming is something beyond what even classic teas can offer.

“Double-roasted”, he mutters…we find out later that he himself has a little ‘lab’ that he disappears into with batches of good harvests to try his hand at a little alchemy once in a while. This is a batch that he created – a two-year-old November harvest that he took a portion aside of and roasted immediately. A year later he re-roasted it carefully – a mere 2 kg’s in total that on our day of drinking a little under a kilo still exists.

We leave with Mr. Lu telling us we have consumed three great Dong Ding’s and making the point that none was necessarily superior to another, but acknowledging that we were treated to one in particular that hitting something a little divine in the mouth.

The random and concluding chaos of any good tea session, the remnants and dregs…that sit and wait for another session

Such are the all too infrequent brushes with a tea whose ‘everything’ comes together…and someone who is willing to share. Leaving the comfortably chaotic office before dinner, I decide not to eat and leave as much of the taste in my mouth as possible for as long as I can manage.

For the present though, my vista has yak continuing to move by under a big Qinghai sky.

Horses, Blue and a Rail

Qinghai or for the Tibetans, Amdo – Michael and I have entered from the eastern Gansu border by that ‘everywhere’ mode of transportation in this part of the world, the bus. The struggle is as usual present; coming out of rugged, silent hinterlands and into a world of chaos and hordes where the mind has to cope with what is and isn’t essential…and much is very ‘unessential’.

Our collective intention is clear and we make haste to get ‘out’ of the city and into big sky country where horizons are a clear line…the moment we arrive to the dusty bulk of the capital of Xining, we hire a driver to take us west to a lake that is known to Mongolians as Kokonor, to the Tibetans as Tso Humbo (Blue Lake) and to the Han as Qinghai Hu. It is regardless of its name the largest lake within China proper and our direction is northwest towards Gansa, which lies northeast of the great blue liquid mass.

On one of Gansa's many corners a gaggle of men sell everything that the local land provides, including what we know as Cashmere and yak wool

Gansa seems to have erupted out of a flatland. Like many locales in these slightly destitute lands one needs an imagination (or perhaps it is my need to find a more pleasant memory of the place) to try and see beneath the newly erected plastic looking façade. There are always the tell-tale shacks and buildings on the fringes which hint at what once was and Gansa is no different. Everything is ‘new’ but little of what we see is at all natural looking. On the outskirts of the town mud huts and tents become the norm, though I imagine they too in time will be something of the past.

Nomads homes offer up proof-positive of the old adage of what is not essential is not taken. A small solar panel rests atop the solid structure

After a night spent in a room smelling of a century of dirty socks, along with a bizarrely ornate rug, we are up the next morning with a bit of zip and fire in us…we will head into the high flatlands, back into nomadic country. Regardless of aches and tiredness that filters down through the days, we are always primed whenever we are heading into ‘empty’ lands.

Off to the right of the road we have been thrown around upon for hours, a multi-coloured collection of nomads huddle. Ornate braids line women’s backs, broad shouldered men with knives which hang in a kind of reckless homage to the past days of fast wits and faster hands.

Horses stand in knots, gleaming and frisky. The highlight of this informal horse festival will be a series of long distance races much as they do in Mongolia – the horse and riders are matched and in many cases the four-legged winner might have offers to buy it. Much of Mongolian culture influenced and even conquered these portions, only to fall back into the equally formidable locals’ hands.

A horseman arrives with his four-legged mate at the end of the race exhausted. He is bareback on the horse in a tribute to the past

A horseman arrives with his four-legged mate at the end of the race exhausted. He is bareback on the horse in a tribute to the past

Deeper we travel into the angled mountains and rains track our progress. Earlier we had been held up on our journey when, with no warning whatsoever, a nomad weaved his motorcycle into our path. What I thought would be an epic crash became a nasty crunch as bounced him and his bike a metre or two. Clearly the nomad’s fault prevailing laws meant that our driver was ultimately responsible and what ensued is part of the great theatrical web of this part of Asia.

After we made sure that the nomad driver was ok, part two of the performance begins with recriminations flying back and forth in a kind of gentle aggression…everyone knowing all the while that our own driver will have to pay up some kind of compensation.

People gather at the sight of our unfortunate accident. The gathering increased pushing up the amount that would be payed - such is the way here

Fellow nomads file in and soon the entire road is blocked with people stopping to get in and see the action – even in this remote little corner or the world. There is one point, one brief moment when I wonder if things will get a tad nasty. A bulky Tibetan who has arrived late, wired and entirely drunk, tries to reignite the entire drama by insinuating all sorts of things. Cooler heads prevail ultimately and a fee is payed and the nomadic driver is shuttled off to mend the leg.

Wandering along I often think on the ways that geography affect the mind, the lives and the aspirations of people. Here with sheer masses of ‘emptiness’, where the sky and earth and yak dung come together, everything seems tangible and touchable. I wonder too if this isn’t one of the reasons (and draws for me) to these lands and peoples – that they are so tangible.

Given this space this way of living, it is hard to imagine a ‘people of the earth’ without their traditional ways.

Given this space this way of living, it is hard to imagine a ‘people of the earth’ without their traditional ways.

At one point off to our left a straight line seems out of place on the huge gap of space. Finally and almost impossibly it comes into focus. A railway coasts above the landscape on stilts. Even here amidst all of this green and sun this sleek transport convener finds a home. We continue until finally the rail and its geometry happily disappear from our view.

A railway line out of nowhere bisects the valley

A railway line out of nowhere bisects the valley

Jeff Fuchs to headline “Explore” Series at Bookworm in Beijing

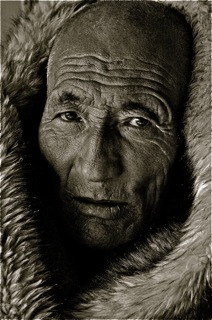

One of the very special 'lados' (muleteers), whose memories alone keep alive the ancient tales of life along the great trade routes

Delighted to be the opening speaker at the Bookworm’s Explorer Series this coming August 2011, in Beijing. Privileged to be able to share. Will be talking (and on occasion ranting) about two routes (and their precious people and memories) that certainly rank among the most arduous and hallucinatory journeys on the planet, the Tea Horse Road and the Tsalam (Nomadic Route of Salt)…and of course I’ll be plugging my favourite green leaf – tea.

Click here to read about the Bookwork events

Click here to read about the speakers

The faces of the remaining traders and travellers, themselves are geographies of effort, gained upon the highest of highlands

The Way of Heights

A sight and activity repeated twice daily – milking. Tibetan tents and compounds are usually erected facing east…and the rising sun

Informality amongst nomads, and that feeling of immediate and informal acceptance comes from their own necessary and inevitable informality amongst themselves. Sickness, births, joy and efforts are shared in real time every day of every season. Bonds are strong and all is shared, and though disputes arise, the lines of communication are entirely direct and open – otherwise the way of the nomad would crumble quickly. Intimacy here is perhaps unromantic in the western sense but it seems to be entirely ‘intimate’ and authentic.

Michael and I wander out of our tent and onto the crunch of frost on the grass. We have set up our two-man tent just outside of the main entrance to the family’s. Space is needed for the crush of bodies that our group of five brings.

Sun (nyeema) and its rays have only started touching the stiff grass but already the yak have been let loose off of their tethers and are making their way off to the highlands, munching as they go. A few are still tethered with yak wool bindings around their legs as hunched bodies milk them. Smoke streams out of a dozen tents, wafting up-valley slowly – no winds have yet touched us. There are few silences like those that the nomads wake to every morning and speed means nothing – here everything is paced according to ancient memories.

Chura, the sour yak cheese of the nomadic areas, lies under the sun. This was and still is often used as a form of protein and added to butter tea

Songjem’s family moves far less than some of their nomadic brethren upon the plateau. They have three dwellings all within ten kilometres of eachother, and their summer and spring areas rest within the same valley corridors. All of their ritual movements are for the benefit (and driven by) their precious yak herds and their frugal needs. For Songjem, the fact that his children and their families are so far is something sad, but there is no hesitation in his voice when he affirms, “yak needs override people’s”.

A nomadic woman’s life is made up work, sleep and more work in a schedule that would break most mortals...but only most

Huge yak herds are the norm here in Gansu and much of nearby Qinghai, with hundreds of yak making up a herd or group. The larger the clan the more yak are likely to be present and the more yak, the more sources of income for the nomads.

Caterpillar fungus, an medicinal root called Beemu, chura (yak cheese), yak meat, yak wool, and sheep and goat wool make up the bulk of what can provide revenue and all of it is seasonal.

What has repeatedly refreshed and inspired me over the years (though the nomads themselves often don’t agree) is how they know exactly what is and isn’t important in their lives – there are few ambiguities. If a child is chosen to go to school, and one or more aren’t selected there is rarely dissent. In fact there is sympathy with the student who must leave, as they “will be alone and away from us”.

Every day, without fail, bodies emerge morning and night to set loose, or tether the herds. Even amidst herds of hundreds the nomads can determine how many (and specifically which) yak are missing in minutes

During a communal family get-together, Songjem stretches out his languid body in the grass and the entire clan blends themselves into the turf. Words are sprayed out with that warm nasal sound and undulating tones. Even their words, spartan and frugal though they may be, are infused with passion and meaning.

A young nomadic man, along with Songjem in the background corral the enormous herds of yak and count them

There is a rhythm here in these grand spaces and a feeling amongst the nomads that though there is much that isn’t understood in the world beyond, there is an absolute understanding of the elements within it…and when they don’t comprehend shifting weather patterns or a plight, this is where the ‘fates’ and the spirit world arrive to assist.

Yours truly indulges (which later turned into over-indulging) in some sho, the local curd-yoghurt specialty, where the tongue becomes the instrument most active.

Songjem in his effortless and very real eloquence sums up one day’s end when I ask him about what he thinks the future holds, “the health of family, yak and our way of life – that is all I can worry about”.

Yaks, Creases and Nomads

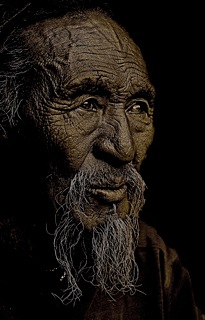

The man we pick up in Nyimalung has the calm eyes and weathered face that the mountains create and sculpt almost at will. Songjem is in his early sixties and his face and countenance have a lived in quality that seem universally recognized; appreciated for what it shows. We head south towards Gansu’s border with Sichuan. Somjem is one of those absolute necessities in any travels in this part of the world – a one-man source of tales, geography and of that rare quality in the modern rush, calm.

He will be our informal guide to the Maqu area, where we are headed. Maqu has yak, goat and sheep in quantities that almost nullify the landscapes…it also has nomads that have long lived amidst the rolling hills. Our old friend, the Yellow River (Ma Chu to the locals) coils its muscular way east acting as an accidental guide to our own wanderings.

To Michael and I, the Yellow River, to the Han Chinese the Huang He, and to the Tibetans the Ma Chu (Peacock River). Whatever its name, its presence and influence were always with us

Maqu is yet another crucible – a town that now sits where two main roads collide. No trees interrupt the horizons; and there are many horizons cut by the hills and mountains. While travel along the main road takes time, once we hit the dirt tracks south of Maqu – which access the nomadic bases – we are lucky to hit a top speed of 10 km’s per hour. Valleys are little nations of nomadic communities with the telltale black tents and sprays of black herds of the precious sok (yak).

Here, there are the dual forces of magnificent green highlands contrasting with rampaging winds which take sand from nearby sand dunes and hurl them to every point of the compass. Along the dirt tracks nomads fly upon their motorcycles with a reckless competence that inevitably brings an admiration. At one point a dozen motorbikes partially block the road. Our little group stops to take in one of the Plateau’s great annual ‘harvests’ – sheep wool. No electric clippers here, no pens to steady the flapping bodies, just an ancient aptitude with the hands and a strategy that is fool-proof. Men and young boys fly around with yips and yells corralling the sheep with a long strip of white canvas which is set up to create a three sided box. One by one the agile sheep are grabbed by a hind leg and dragged (and in many hysterical cases drag their ‘draggers’) out to be bound by foot in mere seconds. This done, one of four seniors in the group wields a spectacularly massive pair of scissors and relieve the sheep of their rangy coat. At one point a young boy insists on displaying some of the native skills, which make the nomads revered as pastoralists and ‘hardmen’ of the mountains. No more than six years old, he, with his lean and toughened little body, attempts to grab the hind leg of an equally youthful sheep only to receive a flaying hoof that takes the little boy in the mid-section with a lightning thump. There is a huge roar of approval from his peers urging a continuation of the festivities.

More than a match for the little boy the young sheep has the kind of desperate power that makes prey far dangerous than one might imagine. The boy’s clothing and expressions are running the full gamut of colour and dirt until finally (with some very needed help from his colleagues) he manages a vice grip on the sheep only to discover that even with three free legs animal is simply too agile and high strung to ‘take’. Here in this region, this tradition of wool harvesting takes place once a year and as with much in the lives of the drok’pa (nomads) work is injected with a communal sense of unity and fun. IMG_1658_2.jpg – Our arrival to a great valley hemmed in on all sides and to Songjem’s clan and their enormous herds of yak The language flying around is the nomadic dialect that rings with intonations and nasal grunts – the lingua franca of the spaces beyond cities up ‘on high’. Simultaneously brash and vulnerable the nomads take life by the literal and figurative horns and live it intensely; there is no other way at over 4 km’s in the sky. Almost four hours later we arrive to Somjem’s clan and their sprawling valley summer abode of streams and insulating mountain peace. There is the clasp of hands and the kind of non-fussy joy of a genuinely happy reunion. Somjem, like so many of nomads I’ve met doesn’t make introductions immediately; he is taken with his own pleasure and that of his clan. IMG_1650.jpg – Valleys lead into other valleys, which in turn lead to smaller valleys and pockets, and each one resides a nomadic community for the extent of the summer We are almost immediately served up thick and potent ‘sho’ – the thick curd like yoghurt offered up (and taken) in heaps. The tang grips and almost stings the tongue. Like everything on the homestead, it is fresh. We sit around a stove that gives of the acrid almost narcotic waft of yak dung burning.

Gansu – Towards the Hills

Michael and I are back in our beloved hinterlands driving deep into the nomadic territories of Gansu province. Continuing my travels into the frontiers to witness a very special way of life change. In this part of the world at least the frontiers are often both the most dynamic and the most remote – change and the modern world’s goodies come swiftly but seem at times to miss entire landscapes and valleys.

Arriving to Lanzhou by flight we have little interest in remaining. Our destination is southwest to Linxia for the night, which will provide a stepping off point for our journey further south into the remote highlands in and around Maqu.

The province has long been a blend of Hui Muslims and Tibetans – trade and mountains are (like many of frontiers along the Tibetan plateau) an inevitable part of the vibrant history of the place. Linxia is seeped in dust but the speed of life is, what I’ve come to love in any lands that are slightly beyond the attentions of the masses – slow and ‘human’.

Hui ‘Halal’ restaurants line the streets, tidy shops somehow remain dust free and the colourful kerchiefs set off the slightly exotic featured women. The Hui have long mastered business dealings, operating as middlemen where few others would tread. Disciplined and unified the Hui offer up a tantalizing history of perseverance and toughness.

There is in Linxia a feeling of spartan efficiency and the sense that the people have learned to thrive and survive with less – the only hints of opulence and ostentation are the seemingly endless mosques, which erupt in every roadside town. Ornate and symmetrical they offer up a little bit of something borderless, and contrast to the lush greens and endless rolling mountains.

Michael and I spend the night in one of those bizarre hotel rooms that one often finds in China – cheap, clean, with very suspect ventilation and faucets. Restless to get out of the city and into the mountains we find a driver who will take us to Maqu into the beloved hinterlands.

Morning comes with the soft lush sounds of the Mosques’ call to prayer, and our driver, himself a local Hui Muslim, whisks us off in the famed and fabled ‘mien bao che’, a tiny van. We know now that the hills are coming and the start coming fast.

Mountain Passes – A Mountain’s Memories

Peaks and mountain spires often steal the dreams and minds – with billowing snow-encrusted lines, thin-aired risks and altitude numbers that defy the mind. Lying beneath these heights wedged and curled into the main body of mountains lay worlds that contrast with their daunting cousins above. These are not the worlds of barriers and blockades; they are the worlds of movement and routes.

Entry point into the Salween Divide, Shar Gong Pass in eastern Tibet is a gateway that for much of every year is blocked by snow

Valleys and passes have long been taken for granted even though it has long been their linking lengths and ushering forces that have funneled bodies into the great mountains. One crucial facet of the mountains, quiet and rarely mentioned in western chronicles remains an essential in any of the globe’s stone faced heights, still: the pass, or in the words of Tibetans, the “la”.

On a recent expedition along the nomadic Salt Road (Tsa’lam) in Qinghai province (Amdo) the importance of the pass was once again made clear. Known to much of the Himalaya’s population the word ‘la’ has long been a suffix attached to the end of every pass worth mentioning…and for mountain-bred people the passes are always worth mentioning. Named for deities, attributes or otherworldly qualities the passes are the gateways to beyond.

Upon the Salt Road distances were measured not simply in days and weeks but in the number of passes or valleys crossed. Too often (particularly in the west) the paths, the routes and the striating strands to pass through the mountains are overlooked, as the race to cross a range, summit a peak and ‘attain’ a mountain dominates interest. For the those living within the domain of the mountains physical geography wasn’t (and still isn’t) simply something to surmount, surpass and struggle against; it was/is a way in which journeys and lives are measured. Geographies are inevitabilities.

In the sage words of a nomadic trader I met years ago, “it is in the valleys and passes below where the stories of the mountains are written”. It is also within the valleys and upon the passes where successful travels and efforts to cross the mountains are forged…or find their undoing.

On the Tea Horse Road, an eight-month journey that occupied (and still does occupy) my mind and body, the 1500 km portion between Gyalthang (Zhongdian) that myself and five local Tibetans took, again and again we heard the names of the famed passes from the mouths of traders. Sho la, Shar Gong la, Nup Gong la, Banda la, Tro la and Jelep la….these names of passes rang within us, as much demarcation points in the mind as they were on the land. A good friend of mine, who has long joined me upon my mountain wanderings once said to me “for every famous peak, there are dozens of more important passes”. I took these words to heart for it was the passes and valleys that most often described a geography’s character.

Known to the Tibetan muleteers as Tro la, Crying Pillar Pass was one of the final passes before reaching Lhasa. It was notorious and took a great toll upon lives...valleys of bones lie nearby for those who weren't successful in crossing its five thousand plus crest.

The famed “Tro la” marking the western most exit point from the Nyanqentanglha Mountains in central Tibet is translated into “Crying Pillar Pass” because of the physical grief it caused caravans. Upon our own ascension of the this five thousand metre pass, we initially smiled as we gazed upon it – smooth and un-technical it struck us as a pass that could be surmounted in a couple of hours.

Half a day later we were still hauling our withering forms over its shale-covered surface. It had, as the legends said, taken every last breath and piece of sinew to ascend with our packs bringing us to a point of near defeat.

The beauty of mountain legend is that most of the origins derive from the tangible experiences that befall and inspire the body and mind. Mountains and their wide domains are rarely (if ever) theoretical or ambiguous.

Mountain passes are still used by wild life and migrants and provide access routes into valleys rarely seen like this one near Litang's Genyen Mountain

Summiting a peak brings one to the pinnacle, and to an end point; making one’s way over a pass conversely shoves the world of senses not only into another frame, it sets us to go further on into another journey through another geography.

Upon the Tibetan plateau, people often refer to eachother by origin, going so far as to differentiate those who live in the valleys as ‘rom’ba’ from those who live in the wind carved heights ‘drok’pa’ (nomads). The rom’ba are known for their playful tales, sense of humour and singing where as the drok’pa are viewed with trepidation, for their fierce abilities in the arts of war, and a primal toughness.

Geography was and still is, much more than simply something that the eyes and ears take in, it provides a very unambiguous ‘shaper’ of peoples and their views.

When one ‘arrives’ to a destination within the mountain realms, the arrivals are inevitably met with questions about the journey – there are rarely comments on the peaks in their distant heights. It is the passes and valleys which are most frequently referred to, for it is here where the travelers’ journeys succeed or fail.

Passes are often as dramatic and fierce, as dreamy and hallucinatory as any peak and certainly for the secular world at least, they are the domains about which tales are most often told.

Interview with Jeff Fuchs on Tea and Co.

Pour yourself a cup of tea and click here to read more about Jeff’s very subjective views on tea.