Our two yak stand still in the blowing white snow; around them there is nothing to suggest a specific time-period and looking at their ice-encrusted wool I imagine a time long ago when gas-spewing, noise machines on wheels hadn’t yet taken over – where movement on land required the foot or hoof. Here, now, in this blowing snow beneath a mountain it is remarkably easy to imagine this time. Amne Machin is just over on our right behind veils of snow and wind.

The yak stand before us resigned and powerful, and it is evident that it is in their DNA and memory banks to wait, to be loaded and to traipse where few beings can. Mobile, tough and silent they provide the broad backs for transport. Nomads delight in riding horses but in these parts no other ‘transporter’ can predictably claim the reliability title at altitude as can these behemoths.

Apart from the yak, all things seem in rapid motion. Snow is contorting and rushing at us from above. The headwoman of the village is continuing to issue orders, while simultaneously tightening up yak wool cords around our gear.

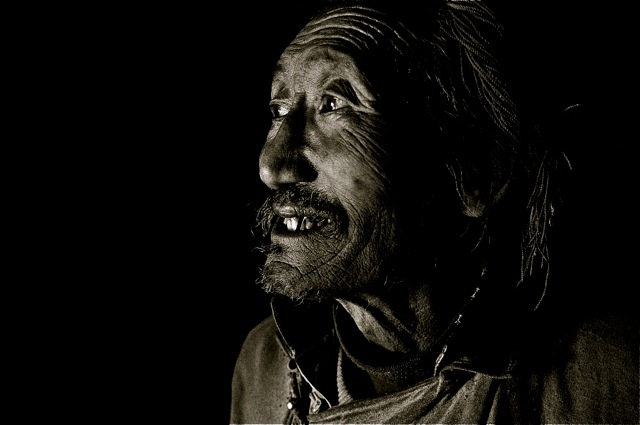

Ancient and essential, the art of loading and tying gear to mules or yak’s backs is something that has long been prized and traders often picked their muleteers or ‘yak-men’ based on their abilities in this skill. Our guide Neema, a short and slight man whose face wouldn’t be at all out of place in the Andes of South America is organizing our food and necessities into bigger bags that will also be tied onto the back and flanks of our yak. One item, an essential given the time of year is a double reinforced bag of dried yak dung patties – fuel for our life giving fires. We are above the treeline here at almost 4 km’s in the sky and the areas where we will tread will not yet have herds of yak…nor their vital ‘droppings’ for us to use.

Huge flakes of snow explode into moisture as they pop against our jackets, and the mountains around us (that we can make out) are already building up their coats of white. The snow is unrelenting and it is hard to imagine a world without white. The winds are crafty, coming at us from all angles at once it seems coming from around Amne Machin.

Making our way out of the valley our vistas open up, but not our sightlines. They are paralyzed by drapes of white snow. Our contingent of moving bodies has somehow become eight bodies. The two yak seem to know precisely where they are going silently leading the way. Neema has mounted a chestnut pony – a lanky tough looking creature, and two dogs have joined along. One dog, a beige 10 kg livewire of energy looks part terrier and part fox, carrying a small diagonal scar on his snout which gives him the look of a seasoned street fighter.

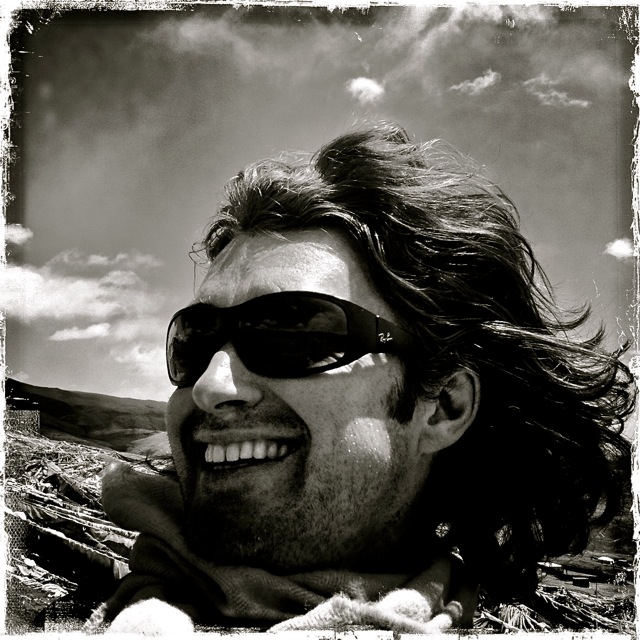

The second dog, a Tibetan mastiff carries his black bulk easily and has the most forlorn brown eyes I have seen in a long while. Michael is wrapped in a black hood and I am encased for the wind and snow. Snow, as it does has at once darkened the entire day and made it so bright that we need the sunglasses for the glare.

Squeezing through a last bottleneck of space, we make out a hazy outline coming up to our left. Unseen to our right, down a plunging valley is the Nam River and the structure to our left, which clarifies as we approach, is the Ge Re Monastery, a new monastery that reminds me strangely of a mosque in shape. It sits as sort of a gateway into a bigger world beyond. It is still in the onslaught of snow…everything but the snow now seems still.

Our roving dog pack has become three with the addition of another old mastiff who shuffles along with us, limping from an old wound. The grey sky above shows no signs of relenting and I’m not sure I want it to…it fells fresh and cool on the face as though the snow is welcoming us into its realm. Our dogs seemed to revel in the adventure.

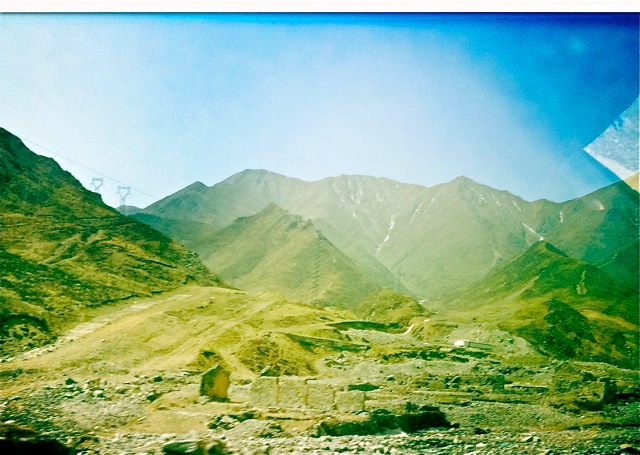

At one point shortly after noon there is the sense that we are entering a massive valley. An ever so slight ebbing of snow temporarily reveals a huge widening in our space. Black streaks of tone stand out in the white and these black streaks go skyward. We under the mountain’s bulk now. Immense and deep, a good portion of the earth that we see has been scrubbed and carved by glaciers. In the white it looks like undulating cream, while never losing its slightly ominous appeal. Our canine population grows another member; yet another mastiff and it is starting to feel as though we are small army of bodies.

We are ‘treated’ to a demonstration of our little terrier’s talents. Regardless of the onslaught of snow, the high mountain rodents, ‘avra’ are busy. Tiny bundles anywhere from 500 – 1000 grams they stand no chance of survival once our little scruffy friend targets them. It is clearly in his blood to hunt and his alert energy is rampant. He has no interest in supplementing his diet….his intention is to utterly destroy the little balls of life. The larger dogs watch in earnest and clearly he is the acknowledged master of the mountains. Amne Machin clearly favours him.

Neema, just after lunch, suggests we lay up and make camp due to the snowfall and cold but Michael and I feel it is better to push on and get a decent first day in. We prevail and continue.

Our route is taking us through dunes of snow on either side of us and though aware of the mountain off to our right, though we can almost make out a white line in the very white sky, we cannot quite see it.

It is a day where the highlights are muted by continuous snow – interspersed with manic bits of entertainment from our little terrier, who we have now (for reasons not needed to explain) have called ‘Ripper’.

In a flurry of running legs at one point, our canine comrades shoot left, their dark bodies bounding through the white. Up higher on a ridge the elusive and incredibly fast ‘Gwa’ or Tibetan antelope flash almost invisibly to a higher point. The dogs will never catch them and return later looking visibly worn…all except our Ripper who seems to have a limitless engine.

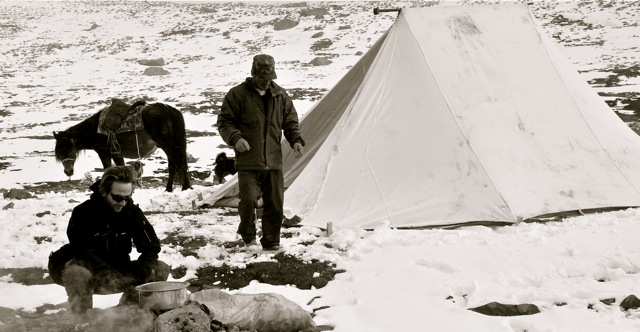

Late afternoon brings more cold and sees an easing of snow. We decide it best to pitch up and remain for the night. Our site is a valley next to an ice-cold stream. Our tent, a small teepee-like canvas unit will provide little resistance to the wind and we have little in the way of ground sheets.

With the snow thinning, the temperature seems to plunge and the sky goes a purplish hue and at last we can see beyond a hundred yards. The mountain opens up before us to the left and right spreading out. The valley that we have been travelling through is split by fold after fold of mountain ridge, wandering off until the earth meets the sky in a tiny smudge of pink.

The Mastiffs lie apart from one another around the tent while our terrier seems intent on planting himself inside the tent. A kettle is put onto our dung fire for boiling water…the one vital to Michael and I. Amne Machin looks at us from above.

Bedding down in a still and frigid cold night, our breath comes out in thin white streams and I feel a little four legged body jam himself under my covers and settle with a growl.