Sour Tea: The Indigenous World’s Treat

Within the muggy mists of eastern Burma, amidst the toughened and muscular indigenous minorities of southern Yunnan there can still be found tea traditions that transcend any tea trends, eras or pretentious terms. There are traditions in these slightly spooky mountains that can literally draw a line directly backwards in time to when tea was more than simply a handful desiccated leaves thrown into hot water. Tea hype doesn’t mean anything here as there is no need; tea is and always has been firmly entrenched here in the very blood.

The ancient Pulang people are viewed, even by the tea savy Dai and Hani peoples as the first indigenous people to cultivate and harvest teas from the remote southern sub-tropics of Yunnan. Some tea academics even attribute the “Pu” of Puer or Pu’erh tea to the Pulang people. Whatever truths there are in tea’s unwritten history, the Pulang people know tea. They know it with a kind of relaxed competence of the truly erudite. They may not have statistics (though increasingly they do) nor coy tea terms but they live with, harvest, speak to and drink tea with an inherent and ancient kind of acumen.

The region’s bitter harvests are enamel-challenging bursts of supreme ‘green’ power, known for astringency, and straightforward ‘bite’ rather than any ephemeral subtleties. These are teas that for many are the ultimate ‘teas to age’ – losing some of their famed bitterness only after a year or two, becoming slightly smoother and becoming a in many cases a classic.

“Traditional dwellings like this are fading from view and to find traditional Hani, Lahu, Pulang and Wa homes must push further into the mountains…tea mountains”.

Travelling west out of Menghai, out of one of China’s great tea gathering points in southern Yunnan – along a road that bends and sometimes pretends to be a highway – a small veer right on the road appears. A rough dirt track that erupts with errant stones and potholes leads northwest – it is a little road that is easy to miss – another path in a landscape of paths that apparently leads nowhere. The difference is that this little route leads to a ‘little tea somewhere’.

Either side of this little sub-road, a complete green landscape of tea bushes take over, soaking the entire horizon in green. After a couple of kilometers and a small rise in the road a bizarre community sits waiting. On the left an enormous tree acts as informal sentry and covers a wide dirt area. A narrow staircase wanders up towards a Buddhist temple.

Nongyang to the eye doesn’t really qualify as either a village or town – it seems to occupy a larger space than it does. Half the community seems ancient while another half is under some sort of modernizing renovation kick. One look at the townspeople though is enough to determine that things are still very much traditional. Dark skinned, powerfully built and almost sensuous features adorn the local people.

It is for the tea-obsessed, a place that continues a tradition of tea preparation that testifies to tea as a food, as medicine and as something very much more than a beverage; it testifies to tea as something utterly sublime.

Up some stairs I enter onto a village version of a terrace, with laundry, shoes, a massive machete and a party of gorgeous dark children fearlessly attacking eachother. The headwoman (whose name is ‘Soon’) of the house (I have long observed that every home has one leader in these parts…and the leaders are women) is square jawed with a powerful little body and a stunning smile that makes the bones ache.

“Soon, a moment before she unearths a massive bamboo husk of year old ‘sour tea’”.

Here in these remote parts, along the roughly drawn border regions of Burma and Yunnan, one of the great tea traditions lies intact, though barely. An edible tea, sour and aged within a bamboo trunk beneath the earth for months or years…only to be dug up cracked open and served with rice: suan cha (sour tea). Long ago the nobles of what is now Burma indulged in lephet, a similar edible tea dish served cold that was often mashed together with spice, roots and anything that lent the tea a tang.

Today however, I will sample something without additives, something literally buried in the soil to ferment and stew, encased with only itself and the damp surroundings as company. It is the local Pulang version of sour tea.

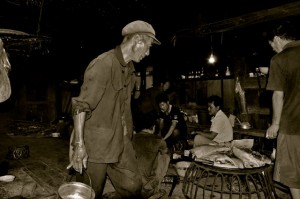

My hostess wrapped in a sarong and a bright headdress sits by a massive pot and begins the process, which despite its exotic reputation, is simple and entirely straightforward.

A smokeless fires burns hot under the pot. The pot itself is maybe one-quarter filled with water, and is being brought carefully to a seething boil. Freshly picked tea leaves are randomly thrown into the burbling water and stirred with chopsticks. How my competent hostess knows the time that it takes to make the leaves soft, but not ‘dead’, is a skill passed on from parents to children and so on. This tradition is being lost, as so much within the cultures that live close to the land is…a slow ebbing halt of transmission, a slow death as fewer youth are interested in archaic (though thoroughly) wonderful processes.

“Soon waits for the raw tea leaves to become more supple within the boiling water. Fires are still made on the floor and much of the family life takes place around the hearth”.

“There are no ‘times’ with preparation of ‘suan cha’, I simply know when the leaves are ready”, Soon tells me later.

Indigenous peoples have this wonderfully liberal description of time as though a defined time is somehow false and unnecessary. Later she peers into the steaming leaves and water elixir and nods her head – it is time.

Draining the water out, the leaves remain in spinach-like in a soft steaming heap, supple and somehow drained of their dark green tones. Soon then uses chopsticks to roughly jam the sodden tea leaves into an empty bamboo husk. Every once in a while she plunges a rough piece of wood in to further break up the tea leaves, compressing leaves into a blend where no air remains.

“Tea leaves, softened and pliant after being boiled are ready for the immersion into the bamboo trunks”.

Drawing up from her squatting position, Soon the then grabs a bag of red clay-like earth, mixes this with some water and creates a kind of cement seal on the end of the bamboo container. Atop this she lays a morsel of aged banana leaf as a kind of second seal. She then beckons for me to follow as she powers down the stairs into the nearby yard.

“Piling the leaves into a bamboo trunk”

With dexterous fluidity she creates an earthen cradle to lay her latest tea creation, afterwards recovering the bamboo husk with earth. Then, without missing a beat she starts digging at another spot that is covered with grass, weeds and flowers.

There is a knock suddenly as her hoe strikes something deep in the earth, and Soon glitters one of those wide smiles that are in themselves a language. A moment later she is unearthing a metre-long bamboo husk utterly encased in damp earth. Soon is uttering chirps and grunts as she rips the shape out….

“Soon takes the ‘suan cha container’, a bamboo husk out of the earth after almost a year in a subterranean tomb”.

It has been in the earth for over a year, but her strong fingers peel off the end leaf and dig away the red earth seal effortlessly.

What appears, filling the container to the brim is a relish-coloured mulch. Nothing at all hints at a ‘tea’ origin.

Bringing the hulking shape back onto the veranda Soon brings a small bowl of rice to me, placing it in my hands. A portion of the earth-bound tea mulch is then put into my rice and I am urged (which is close to an order) to eat.

“What emerges from the bamboo container is a dense mulch-like substance that initially punishes the tongue and mouth, but finds harmony with an addition of rice”.

Sour doesn’t quite do the flavour justice – it is more a bitter mush with tea’s flavonoids only (and barely) kicking in once the fibrous concoction has been swallowed. Taken and munched with the rice though, something happens that more fully opens the palate to other tea flavours. Rice’s sweetness combines and fuses with the aged tea leaves to creat something harmonious.

Soon is nodding her head catching something in my expression before I can fully appreciate what it is. Tea’s base and its abilities to permeate goodness far and wide in yet another way is revealed – Asia’s eternal green strikes again.

When I ask, who other than Soon can prepare this simple potent concoction in the village, Soon responds, “My daughter…but not as good as me”. She seems to lament for just a moment before beaming that big smile again.

“Soon’s inherited skills of preparing sour tea, passed down through generations of oral narratives are finding fewer and fewer who are interested in continuing the ancient ways”.